By Ernie Oleksy and John Evans –

Federal Circuit decisions applying the new standards for design-patent obviousness continue to inform how patent challengers should frame their plans of attack, both in the PTAB and in the courts. In Dynamite Marketing, Inc. v. The WowLine, Inc., the Federal Circuit affirmed a jury verdict holding that the asserted design patent (U.S. Patent No. D751,877 (“’877”)) was not proven obvious under the old Rosen-Durling test that the jury was instructed to apply, or the new LKQ test that overruled it. 2024-1523, 2024-1525 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 12, 2025) (non-precedential). The decision serves as an important reminder that, under the old test or the new one, a patent challenger must always identify a primary reference in evidence and provide a non-hindsight-based analysis to prove that the challenged design would have been obvious.

Background. We have written about the LKQ v. GM case and the landmark en banc decision, which replaced the rigid Rosen-Durling obviousness test for design patents with the more flexible tests under KSR v. Teleflex and Graham v. John Deere. The Dynamite decision, however, shows that while substantive obviousness analysis is no longer rigid, the procedural steps toward proving obviousness remain unchanged. That is, there must still be: (1) a prior-art “primary reference” in evidence; and (2) record‑supported, non‑hindsight reasons for why an ordinary designer would have modified that primary reference to reach the challenged design.

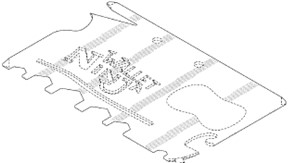

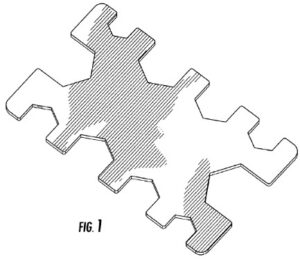

The Designs at Issue. The ’877 patent claims the design of a credit‑card‑sized, wallet-compatible multi‑tool (“Wallet Ninja”). The patent challenger’s expert argued that the ’877 patent was obvious over U.S. Patent No. D603,230 (“’230”) but, critically, testified that it was “probably” the primary reference. As shown below, the designs are noticeably different; the ’877 patent design has an asymmetrical, generally rectangular card outline and cut-out elements arranged along the perimeter and interior, whereas the ’230 patent design is a symmetrical, gear‑like plate:

| ’877 Patent (Wallet Ninja) | ’230 Patent |

|

|

The Evidentiary Issue. It appears that the patent challenger failed to move the ’230 patent into evidence, and even then, it was not unambiguously identified as a primary reference. As such, the Federal Circuit held that the patent challenger’s obviousness defense failed because “the record [did not] clearly support[] the existence of a primary reference.” For that reason alone, the panel affirmed without remand under either Rosen-Durling or LKQ.

Obviousness Analysis. Putting aside the evidentiary issue, the patent challenger’s case had holes under both the old and new legal frameworks. Under the old Rosen-Durling test, a primary reference had to be “basically the same” as the claimed design. As shown above, the overall design and individual design features of the ’230 patent look different than the ’877 patent design, which would have made it challenging to meet the old “basically the same” standard.

And while LKQ made the obviousness analysis more flexible, the patent challenger would still have to convince the jury that the ’230 patent was a suitable starting point (i.e., primary reference) and persuade the jury with record‑supported reasons that specific, obvious modifications would produce the ’877 patent’s overall appearance. As LKQ cautioned: “Of course, it follows that the more different the overall appearances of the primary reference versus the secondary reference(s), the more work a patent challenger will likely need to do to establish a motivation to alter the primary prior art design in light of the secondary one and demonstrate obviousness without the aid of hindsight.” 102 F.4th 1280, 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2024).

In this respect, the Federal Circuit criticized the patent challenger’s expert testimony, which “failed to provide clear and convincing record‑supported reasons” for why an ordinary designer would be motivated to combine specific features from other prior art to arrive at the ’877 patent’s overall appearance, using the ’230 patent as a starting point. Instead, the court rejected the testimony as only a “general hindsight‑based conclusion” and insufficient under LKQ.

Takeaways. Patent challengers must introduce into evidence a clearly-identified primary reference for obviousness invalidity. This threshold failure spells doom under both Rosen-Durling and LKQ. Further, it is not enough to assert that features from prior art designs could be combined to render a design patent obvious. Even after LKQ, courts require record‑supported motivations that an ordinary designer would have had motivation to modify or combine prior art references—without hindsight.

Latest posts by John Evans, Ph.D. (see all)

- Show Me the Evidence: Primary References Still Required after LKQ - October 3, 2025

- Another Fender-Bender between LKQ and GM - July 31, 2025

- PTAB Issues First Post-LKQ Design Patent Decision - September 27, 2024