By Kerry Barrett and John Evans

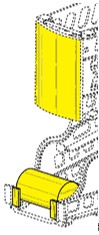

Design patent obviousness requires a heavy threshold burden of proof. Challengers have to find a “primary reference,” i.e., prior art that has “basically the same” design characteristics as the claimed design. Below is an example of an alleged “primary reference” that the Federal Circuit held did not meet the exacting “basically the same” standard:

| Claimed Design | Alleged “Primary Reference” |

|

|

Overall, this alleged “primary reference” looks like the claimed design, but the Federal Circuit held it was not “basically the same,” because of “substantial differences” in its components, e.g., different screen features, frame perforations, and attached elements. Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd., 678 F.3d 1314, 1330-31 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

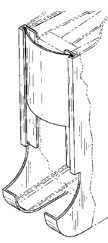

But, recent precedent suggests that the “primary reference” standard may be more flexible about component differences. In Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus, Inc., a Federal Circuit panel majority reversed the PTAB’s determination that the following alleged “primary reference” (Linz) fell short of its mark. Here is one of the claimed designs (claimed parts in yellow), next to Linz:

| U.S. Design Patent No. D612,646 | “Linz” |

|

|

No. 2018-2029, slip op. at 3, 5 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 26, 2019). The PTAB held that Linz was not a “primary reference” because it lacked key features of the claimed design, including, for example, “a cylindrical object below the label area.” Id. at 7-8.

The Federal Circuit reversed because, while Linz does not depict a can, the designs at issue were can dispensers and “Linz’s design is made to hold a cylindrical object in its display area.” Id. at 10. The missing can did not disqualify Linz as a primary reference. Id. at 9-10. And, the other component differences were “ever-so-slight differences in design,” and insignificant “in light of the overall similarities.” Id. at 9.

The dissent challenged the majority’s analysis as “not in accordance with design patent law.” Dissent at 5. The can was, in the dissent’s view, “a major design component[,]” and “[t]he absence from the primary reference of a major design component cannot be deemed insubstantial.” Id. at 6.

This decision may mark a shift in the Federal Circuit’s approach to design patent obviousness that could broadly impact design patent prosecution and enforcement strategies. From an IPR perspective, the takeaways are clear. The PTAB may need to interpret the disclosures of an alleged “primary reference” beyond the contents of its images. This gives Petitioners flexibility to provide a deeper, nuanced analysis of a claimed design and alleged “primary references.” Patent Owners likewise need to be ready to engage on these levels, rather than simply relying on the presence or absence of components in particular images.

Latest posts by John Evans, Ph.D. (see all)

- Show Me the Evidence: Primary References Still Required after LKQ - October 3, 2025

- Another Fender-Bender between LKQ and GM - July 31, 2025

- PTAB Issues First Post-LKQ Design Patent Decision - September 27, 2024