By Kerry Barrett and John Evans –

As with utility patents, a patentee can counter obviousness of a patented design by producing objective evidence that the design was non-obvious, like commercial success, copying, etc. But to be persuasive, a nexus must exist between that evidence and the design’s merits. These legal standards seem simple enough, but they can be difficult to apply as reflected in the Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Campbell Soup Co. v. Gamon Plus, Inc., Nos. 20-2344 and 21-1019 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 19, 2021).

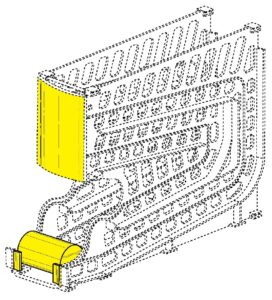

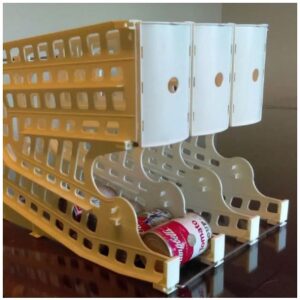

The appeals were about the patentability of partial designs of the iQ Maximizer soup can display:

|

|

| U.S. Patent No. D612,646 (claim in yellow) | iQ Maximizer Commercial Embodiment |

This was the patents’ second visit to the Federal Circuit. Last time around, the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s ruling of non-obviousness and remanded. On remand, the PTAB relied on the patentee’s objective evidence of commercial success, industry praise, and copying to find, again, that the designs were not obvious.

The Federal Circuit reversed for three reasons:

- There was no presumed nexus between the patented design’s merits and the objective evidence. A “nexus” to the design may be presumed when the patented product is “coextensive” with the claimed invention, e., it “is the invention disclosed and claimed.” Fox Factory, Inc. v. SRAM, LLC, 944 F.3d 1366, 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Here, however, the claimed partial design was not “coextensive” with the commercial embodiment, which “undisputedly includes significant unclaimed functional elements …” Slip op at 11.

- There also was no nexus-in-fact. Apart from presumed nexus, a patentee may establish nexus-in-fact by showing that the objective evidence is the “direct result of the unique characteristics of the claimed invention.” Fox Factory, 944 F.3d at 1373-74. But in this case, evidence of commercial success and praise pertained to “aspects of the label area that were already present in the prior art[,]” such as the display label being a double-size depiction of the can label. at 13.

- Finally, evidence of copying did not overcome the strong evidence of obviousness. at 13-14.

In view of the Federal Circuit decision, the main takeaway is that finding persuasive objective evidence of non-obviousness of a patented design may be challenging. It seems unlikely that any design patent could satisfy the presumed nexus standard. By definition, design patent claims exclude functional elements, and thus, patented products likely will “include[] significant unclaimed functional elements.” As for nexus-in-fact, the Federal Circuit seems to have set a high bar, requiring that the “unique characteristics” of the design, as it is depicted in the drawings, must be particularly linked to the objective evidence.

Latest posts by John Evans, Ph.D. (see all)

- PTAB Issues First Post-LKQ Design Patent Decision - September 27, 2024

- Petitioners Beware: Screenshots Showing Product May Not Qualify as Printed Publication - September 18, 2024

- En Banc Federal Circuit Overrules Rosen-Durling Test for Design Patent Obviousness - May 23, 2024